Researching a piece on the multi-agency effort to restore steelhead trout to watersheds of the San Francisco Bay estuary. It's hard to grasp the story because so many agencies are involved, 17 according to Oakland-based Center for Ecosystem Management and Restoration (CEMAR), which seems to be the point organization of the Bay Area restoration effort. Much of the restoration and preservation action is in the south Bay, because that's where the protected land and drinking water reservoirs are. In one of the reservoirs, the one formed by Calaveras Dam, which blocks the famed, popular Alameda Creek and stands seismically unsound to be rebuilt by 2015, live an interesting population of rainbow trout. The San Francisco Public Utilities Commission just started work on the new Calaveras Dam; here's the early Sept. 2011 San Francisco Chronicle article on the dam rebuild project that spurred this whole story idea forward: aqui.

The section from that Chronicle article that caught my eye was:

The rainbow trout in the reservoir are believed to be landlocked steelhead that are descendants of the indigenous fish population, biologists say. Conservationists hope to use those fish as a potential gene pool for restoring the original native steelhead runs.

So, there's some trapped rainbows behind Calaveras Dam that are genetically "itching" to be oceanbound, to be steelhead again? And there's a longstanding effort to restore Alameda Creek's steelhead runs? And Alameda Creek is the third-largest SF Bay watershed behind the San Joaquin River and the Sacramento River watersheds? And there's an historical ecology study of Alameda Creek going on?

And, the motivation for pursuing the story became, immediately - I want to see Alameda Creek and learn more about that landlocked steelhead population, especially since Jeff Miller, director of the Alameda Creek Alliance, listed the Sunol Regional Wilderness, in the heart of Alameda Creek's watershed, as one of his favorite outdoor spots in the Bay Area.

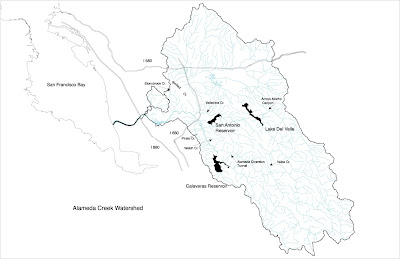

Map of Alameda Creek's watershed.

Map of Alameda Creek's watershed.The big question becomes: Why restore steelhead runs in the first place? Steelheads are, I didn't know this, identical to rainbow trout; steelhead are rainbows that have been to sea, where they earn harder, steel-colored sides and sharper, meaner-looking mouths and heads, replacing the rainbow-y, downy-appearing, peachy coloration characteristic of rainbows. I asked Jeff Miller the key question and his answer is: because it's an indicator species, and it allows a focal point for the restoration of a whole watershed. This answer opened up the story to a whole different level. Especially since, Gordon Becker, fisheries scientist and Bay Area steelhead restoration point-person at CEMAR, said, "They are the species the public grabs hold of the most." If you lose steelhead populations, he said, you lose the public momentum to restore and preserve healthy creeks and streams, which themselves are critical because many people's first connection to nature is, as kids, with their local creeks. True! I explored Boggy Creek next to my childhood home in Austin, Texas, almost every day as a kid. So, the story immediately became a much larger, immediate, powerful one.

Steelhead above, Rainbow below. See how much tougher the steelhead look. They're the exact same fish genetically. Once the Rainbow goes to sea, though, it becomes hood.

Steelhead above, Rainbow below. See how much tougher the steelhead look. They're the exact same fish genetically. Once the Rainbow goes to sea, though, it becomes hood.Steelhead restoration is an avenue to explore the raw, ingenue, burgeoning opportunities to encounter vibrant nature, be fed by it, and begin a relationship that invariably sustains for a lifetime and arguably makes you a better earthbound human. That's the pitch I made today for a Bay Nature feature piece: Steeling the Bay.

Note: Coho and Chinook salmon once had runs in the Bay watersheds, but they aren't being brought back because they're more finnicky spawners; they usually spawn in a stream's headwaters, which in today's heavily dammed and culverted waterways is a nearly impossible obstacle. But steelhead are more adaptable. Indeed, some of the rainbow population in Calaveras Reservoir are landlocked steelhead; as Jeff Miller put it, "They look seaworthy." They're tougher-looking than other landlocked rainbows, like they could head to sea tomorrow and some in the population would make it back to spawn. In Upper San Leandro Reservoir, which sits idyllically placid, pure, untouched-looking just over the East Bay Hills (I see it on my long bike rides bordering a windy, looks-like-it-but-not-so-backcountry road) a good bunch of miles north of Calaveras Dam in the East Bay. Miller says the rainbows in the San Leandro Reservoir have similar "wild" genetics to the Calaveras Reservoir rainbows, but they just don't seem or look as hardy. A 1999 genetics study indeed shows that the Calaveras landlocked steelhead do not have the weakened genes of the five area hatchery rainbow strains, and are closely aligned with those wild steelhead in Lagunitas Creek, a Marin County stream.

San Leandro Reservoir on the right of the image.

San Leandro Reservoir on the right of the image.A new genetics study is going on now, says Brian Sak, San Francisco Public Utility Commission scientist (SFPUC) involved with the restoration efforts in the East Bay. The SFPUC manages Calaveras Dam and its drinking water, lands upstream of it, some as far away as the Sierra. Of course, SFPUC also manages the Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, a whole other, amazing story.

No comments:

Post a Comment